Two new genetic variations of the H7N9 and H7N2 subtypes of the virus found in unvaccinated ducks

After chicken, the bird flu virus has now emerged in ducks in China.

China produces roughly three billion ducks per year, which is not to the scale of chicken production.

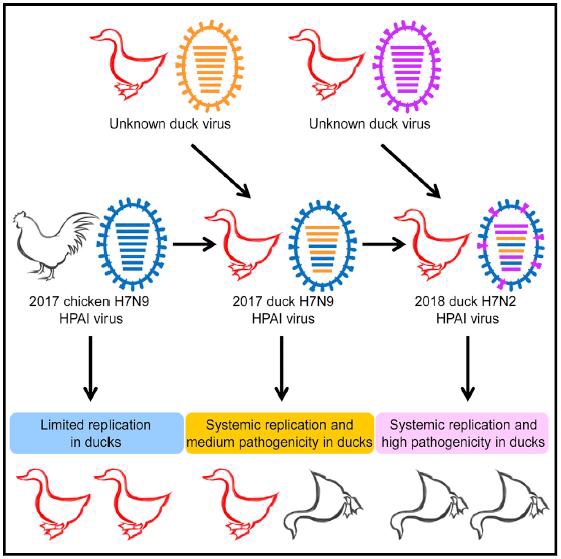

In response to bird flu pandemics starting in 2013, officials in China introduced a new vaccine for chickens in September 2017. Recent findings suggest that the vaccine largely worked but detected two new genetic variations of the H7N9 and H7N2 subtypes in unvaccinated ducks. These findings have been published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe on September 27.

“It surprised me that the novel, highly pathogenic subtypes had been generated in and adapted so well to ducks, because the original highly pathogenic form of H7N9 has very limited capacity to replicate in ducks,” says Hualan Chen, a senior author on the paper and an animal virologist at the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute.

To prevent further human infection, Chen and her team believe that the virus should be eliminated in ducks as soon as possible

Chen’s team collected over 37,928 chickens and 15,956 duck genetic samples 8 months before and 5 months after the vaccine’s introduction. They isolated 304 H7N9 viruses before the vaccine’s release, and only 17 H7N9 viruses and one H7N2 virus after.

“Our data show that vaccination of chickens successfully prevented the spread of the H7N9 virus in China,” says Chen. “The fact that human infection has not been detected since February 2018 indicates that consumers of poultry have also been well-protected from H7N9 infection.”

The bird flu virus replicates in host cells and often mutates and reassorts over time. When Chen’s team looked closely at the genetic types of the disease-causing strains in ducks, they found that an H7N2 and an H7N9 virus had picked up certain gene segments from other duck influenza viruses, improving their ability to infect ducks.

“Influenza viruses mutate as long as they replicate, but it’s very difficult to predict when the H7N9 virus will obtain a particular harmful mutation,” says Chen. “It is possible that the virus may adapt in other species in the future if it cannot be eliminated soon.”

To prevent further human infection, Chen and her team believe that the virus should be eliminated in ducks as soon as possible.

“Fortunately, our study indicates that the current vaccine will work well in ducks, so we do not need to develop a new one,” says Chen. “We suggest applying the H7 vaccine in ducks immediately.”