Blocking estrogen signal in brain may reverse osteoporosis in females

New research shows that blocking a particular set of signals from estrogen-sensitive brain cells, can reverse osteoporosis in females.

These cells are located in a region of the hypothalamus called the arcuate nucleus. Blocking the signals produced extraordinarily strong bones and maintained them into old age. This raises hopes for new approaches in preventing or treating osteoporosis in older women.

However, interfering with estrogen signaling in male mice appeared to have no effect.

Female sex hormone estrogen plays an important role in promoting bone growth and declining levels of estrogen increases risk of osteoporosis in older women

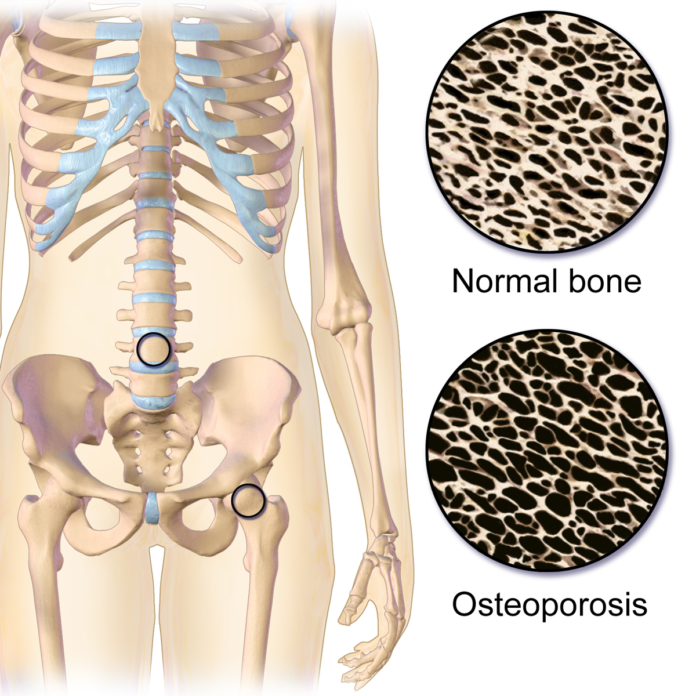

Osteoporosis is a bone disease that causes bones to become weak and brittle. Bones become so brittle that a fall or even mild stresses such as minor trauma, bending or coughing can cause a fracture. Osteoporosis occurs when the creation of new bone doesn’t keep up with the removal of old bone.

Although it affects older men and women of all races, older white and Asian women who are past menopause are at highest risk. Female sex hormone estrogen plays an important role in promoting bone growth and declining levels of estrogen increases risk of osteoporosis in older women.

One in every three postmenopausal women suffer from osteoporosis in the western world.

The researchers found that genetically deleting the estrogen receptor protein in hypothalamic neurons caused mutant animals to an increase in bone mass by as much as 800 percent. The mutant animals’ extra-dense bones also proved to be super-strong.

The authors hypothesized that estrogen must normally signal these neurons to shift energy away from bone growth, but that deleting the estrogen receptors had reversed that shift.

Further experiments showed that mutant animals maintained their enhanced bone density well into old age. Normal female mice begin to lose significant bone mass by 20 weeks of age, but mutant animals maintained elevated bone mass well into their second year of life, quite an old age by mouse standards.

Remarkably, researchers were even able to reverse existing bone degeneration in an experimental model of osteoporosis. In female mice that had already lost more than 70 percent of their bone density due to experimentally lowered blood estrogen, deletion of arcuate estrogen receptors caused bone density to rebound by 50 percent in a matter of weeks.

“These results highlight the opposite roles played by estrogen in the blood, where it promotes bone stability, and in the hypothalamus, where it appears to restrain bone formation,” said senior author Holly Ingraham, PHD.

Scientists are now investigating exactly how this brain-bone communication happens, and whether drugs could be developed to boost bone strength in post-menopausal women. The most important question is if this can be done without potentially dangerous effects of estrogen replacement therapy.

“This new pathway holds great promise because it allows the body to shift new bone formation into overdrive,” commented Stephanie Correa, PhD, an assistant professor at UCLA.

This study by UC San Francisco and UCLA scientists was published in Nature Communications.