Home and folk remedies are often favoured by parents whose children have a cold

Vitamin C to keep the germs away. Never go outside with wet hair. Stay inside.

Despite little or no evidence suggesting these types of methods actually help people avoid catching or preventing a cold, more than half of parents have tried them with their kids, according to the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health at the University of Michigan.

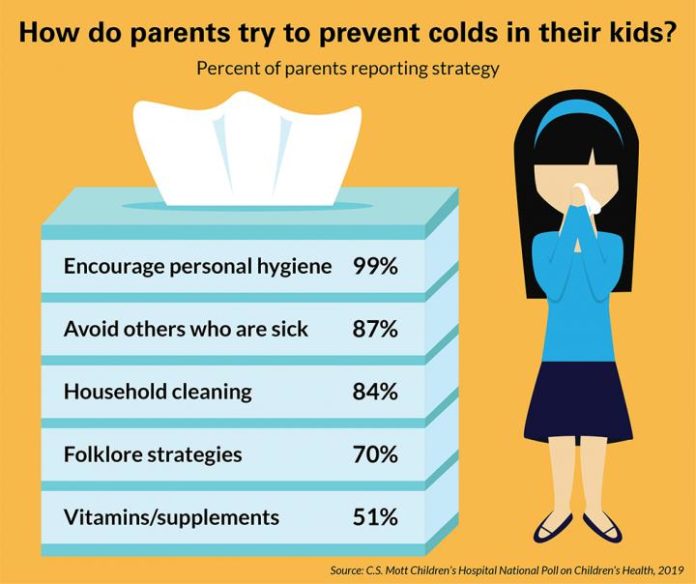

The good news: Almost all parents (99 percent) say their approach to cold prevention involves strong personal hygiene, which science shows prevents spreading colds. These strategies include encouraging children to wash hands frequently, teaching children not to put their hands near their mouth or nose and discouraging children from sharing utensils or drinks with others.

On average, school-age children experience three to six colds per year, with some lasting as long as two weeks

Still, 51 percent of parents gave their child an over-the-counter vitamin or supplement to prevent colds, even without evidence that they work. Seventy-one percent of parents also say they try to protect their child from catching a cold by following non-evidence-based “folklore” advice, such as preventing children from going outside with wet hair or encouraging them to spend more time indoors.

Colds are caused by viruses spread most frequently from person to person. The most common mechanism is from mucous droplets from the nose or mouth that get passed on through direct contact or through the air by sneezing or coughing and landing on the hands and face, or on surfaces such as door handles, faucets, countertops and toys.

“The positive news is that the majority of parents do follow evidence-based recommendations to avoid catching or spreading the common cold and other illnesses,” says Gary Freed, M.D., M.P.H., co-director of the poll and a pediatrician at Mott.

“However, many parents are also using supplements and vitamins not proven to be effective in preventing colds and that are not regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. These are products that may be heavily advertised and commonly used but none have been independently shown to have any definitive effect on cold prevention.”

There is no evidence that giving a child Vitamin C, multivitamins or other products advertised to boost the immune system is effective in preventing the common cold. Freed notes that the effectiveness of supplements and vitamins do not need to be proven in order for them to be sold.

The folklore strategies, he adds, have likely been passed down from generation to generation and started before people knew that germs were actually the cause of illnesses like colds.

On the bright side, even more parents use cold prevention strategies that are supported by science. In addition to helping children practice good hygiene habits, 87 percent of parents keep children away from people who are already sick. Sixty-four percent of parents reported that they ask relatives who have colds not to hug or kiss their child, and 60 percent would skip a playdate or activity if other children attending were ill. Some parents (31 percent) avoid playgrounds altogether during the cold season.

Eighty-four percent of parents also incorporated sanitizing their child’s environment as a strategy for preventing colds, such as frequent washing of household surfaces and cleaning toys.

On average, school-age children experience three to six colds per year, with some lasting as long as two weeks.

“When children are sick with a cold, it affects the whole family,” Freed says. “Colds can lead to lack of sleep, being uncomfortable and missing school and other obligations. All parents want to keep families as healthy as possible.”

But, he adds, “It’s important for parents to understand which cold prevention strategies are evidence-based. While some methods are very effective in preventing children from catching the cold, others have not been shown to actually make any difference.”