Normal immune cells in the breast, it seems, help in the spreading of cancer outside of the breast tissue

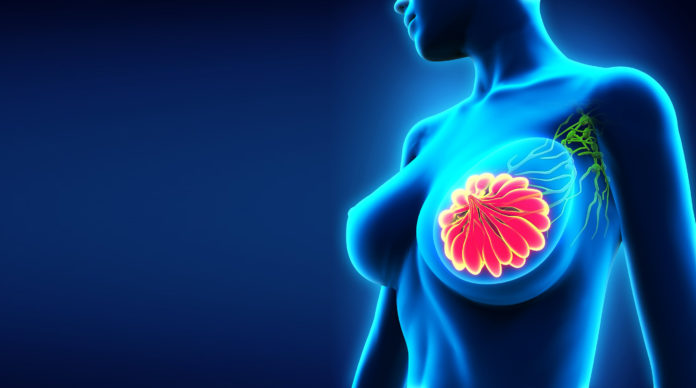

US researchers have discovered that normal immune cells called macrophages, which reside in healthy breast tissue surrounding milk ducts, play a major role in helping early breast cancer cells leave the breast for other parts of the body, potentially creating metastasis before a tumor has even developed. The study was published in Nature Communications.

Macrophages play a role in mammary gland development by regulating how milk ducts branch out through breast tissue. Many studies have also proven the importance of macrophages in metastasis, but until now, only in models of advanced large tumors. By studying human samples, mouse tissues, and breast organoids, which are miniaturized and simplified versions of breast tissue produced in the lab, the new research found that in very early cancer lesions, macrophages are attracted to enter the breast ducts where they trigger a chain reaction that brings early cancer cells out of the breast, said lead researcher Julio Aguirre-Ghiso, Professor of Oncological Sciences, Otolaryngology, Medicine, Hematology and Medical Oncology at The Tisch Cancer Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Early treatment of high-risk patients may prevent the formation of deadly metastasis better than the current standard of treating metastatic disease

This research shows that macrophages’ relationship with normal breast cells is co-opted by early cancer cells that activate the cancer-causing HER2 gene, helping in this newly-discovered role of these immune cells. The findings from this study could eventually help pinpoint biomarkers to identify cancer patients who may be at risk of carrying potential metastatic cells due to these macrophages and potentially lead to the development of novel therapies that prevent early cancer metastasis.

Early treatment of high-risk patients may prevent the formation of deadly metastasis better than the current standard of treating metastatic disease only once it has occurred, said key researcher Miriam Merad, Director of the Precision Immunology Institute and the Human Immune Monitoring Center and co-leader of the Cancer Immunology program at The Tisch Cancer Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“Our study challenges the dogma that early diagnosis and treatment means sure cure. In this study and in our previous studies, we present mechanisms governing early dissemination. This work further sheds light onto the mysterious process of early dissemination and cancer of an unknown primary tumor,” Dr. Aguirre-Ghiso said.

Researchers hope to build on this study by identifying which macrophages specifically control early dissemination. They also hope to further detail how early disseminated cancer cells interact with macrophages in the lungs where metastases eventually form and how this interaction can be targeted to prevent metastasis.

“Here, we have identified how macrophages and early cancer cells form a ‘microenvironment of early dissemination’ and show that by disrupting this interaction we can prevent early dissemination and ultimately deadly metastasis,” said Dr. Merad.