The device closely monitors beating heart cells without affecting their behavior

Scientists have developed an electronic device to closely monitor beating heart cells, or cardiomyocytes, without affecting their behaviour.

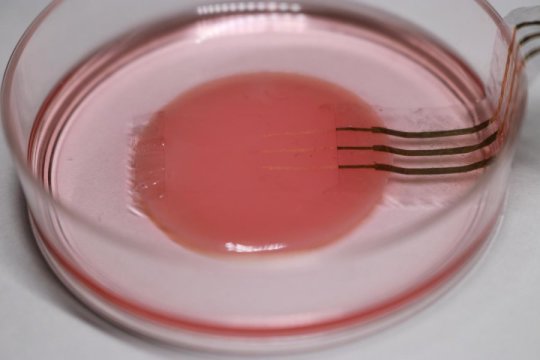

A collaboration between the University of Tokyo, Tokyo Women’s Medical University and RIKEN in Japan made a functional sample of heart cells with a soft nanomesh sensor in direct contact with the tissue. This device could aid study of other cells, organs and medicines. It also paves the way for future embedded medical devices.

Credit: © 2018 Someya Group

Inside all of us beats a life-sustaining heart. Unfortunately, the organ is not always perfect and sometimes goes wrong. One way or another research on the heart is fundamentally important to us all. So when Sunghoon Lee, a researcher in Professor Takao Someya’s group at the University of Tokyo, came up with the idea for an ultrasoft electronic sensor that could monitor functioning cells, his team jumped at the chance to use this sensor to study heart cells, or cardiomyocytes, as they beat.

“When researchers study cardiomyocytes in action they culture them on hard petri dishes and attach rigid sensor probes. These impede the cells’ natural tendency to move as the sample beats, so observations do not reflect reality well, our nanomesh sensor frees researchers to study cardiomyocytes and other cell cultures in a way more faithful to how they are in nature. The key is to use the sensor in conjunction with a flexible substrate, or base, for the cells to grow on.” said Sunghoon Lee, one of the researchers from University of Tokyo in Japan.

Whether it’s for drug research, heart monitors or to reduce animal testing, I can’t wait to see this device produced and used in the field. I still get a powerful feeling when I see the close-up images of those golden threads

For this research, collaborators from Tokyo Women’s Medical University supplied a healthy culture of cardiomyocytes derived from human stem cells. The base for the culture was a very soft material called fibrin gel. Lee placed the nanomesh sensor on top of the cell culture in a complex process, which involved removing and adding liquid medium at the proper times. This was important to correctly orient the nanomesh sensor.

To develop the sensor, first a process called electro-spinning extrudes ultrafine polyurethane strands into a flat sheet, similar to how some common 3D printers work. This spiderweb like sheet is then coated in parylene, a type of plastic, to strengthen it. The parylene on certain sections of the mesh is removed by a dry etching process with a stencil. Gold is then applied to these areas to make the sensor probes and communication wires. Additional parylene isolates the probes so their signals do not interfere with one another.

“Drug samples need to get to the cell sample and a solid sensor would either poorly distribute the drug or prevent it reaching the sample altogether. So the porous nature of the nanomesh sensor was intentional and a driving force behind the whole idea,” said Lee. “Whether it’s for drug research, heart monitors or to reduce animal testing, I can’t wait to see this device produced and used in the field. I still get a powerful feeling when I see the close-up images of those golden threads.”