Gas Embolotherapy could minimise side-effects of chemotherapy by keeping the drug localised for longer

First there was embolisation – cutting off blood supply to cancerous tissue to prevent it from growing. Now, scientists have stumbled upon a way to use gas bubbles, that are used for embolisation, to not just cut off the blood supply but also to deliver drugs.

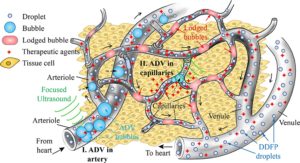

The potential of these bubbles as a drug delivery system has been reported by a team of researchers from China and France in Applied Physics Letters. This is called gas embolotherapy. During this process, the blood supply is cut off using acoustic droplet vaporization (ADV), which uses microscopic gas bubbles induced by exposure to ultrasonic waves.

“We have found that gas embolotherapy has great potential to not only starve tumors by shutting off blood flow, but also to be used as a source of targeted drug delivery,” said Yi Feng, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Xi’an Jiaotong University and first co-author of the paper.

Their findings could provide a one-two punch for cancer treatment — shutting off blood flow from the arterioles and delivering drugs through the capillaries. chemotherapy drugs could be kept localized for longer periods of time

In gas embolotherapy, researchers inject droplets, from tens to hundreds of nanometers in diameter, into feeder vessels surrounding the tumor. Microscopic gas bubbles are then formed from the droplets through ultrasound, growing large enough to block the feeder vessels (e.g., arterioles).

In previous work, the researchers expected to use ADV to starve the tumor by blocking blood flow in the arterioles. To their surprise, they found that the bubbles not only blocked the arterioles, but other gas bubbles made their way into the capillaries, resulting in vessel rupture and more leaky microvasculature.

In their latest work, gas embolotherapy through ADV was performed to further explore the dynamics of the bubbles inside the capillaries. Testing was conducted ex vivo on rat tissue that attaches the intestines to the abdominal wall.

Their findings could provide a one-two punch for cancer treatment — shutting off blood flow from the arterioles and delivering drugs through the capillaries. In addition, chemotherapy drugs could be kept localized for longer periods of time because blood flow has been shut down, reducing drug dosage.

“In cancer therapy research, scientists are always interested in answering two questions: how to kill the cancer effectively and how to reduce the side effects of chemotherapeutic drugs,” said Mingxi Wan, professor of biomedical engineering also at Xi’an Jiaotong University and corresponding author of the paper. “We have found that gas embolotherapy has the potential to successfully address both of these areas.”

With an ultrasound imaging method in place, according to Feng, gas embolotherapy has a good chance of becoming a standard practice. Wan and Feng’s team is working with another group of researchers in the same lab, and such an imaging system is being built to apply the ADV gas embolotherapy method in rats.