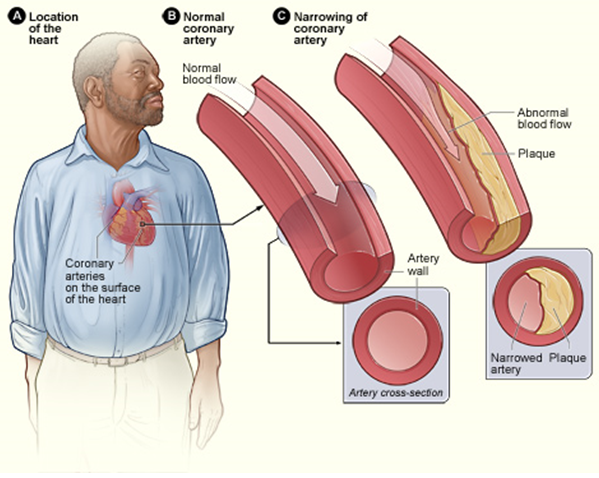

Lancet study finds sharing pictures of scans showing extent of atherosclerosis lowers cardiovascular risk

It is notoriously difficult to get patients at high cardiovascular risk to do lifestyle modifications; however showing them pictures of the extent of atherosclerosis (ageing of blood vessels) could lead to better compliance.

A new randomised trial of over 3000 people in The Lancet found that sharing pictorial representations of personalised scans to patients and their doctors results in a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease one year later.

Smoking cessation, physical activity, statins, and antihypertensive medication to prevent cardiovascular disease are among the most evidence-based and cost-effective interventions in health care. However, low adherence to medication and lifestyle changes mean that these types of prevention efforts often fail.

“Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in many countries, and despite a wealth of evidence about effective prevention methods from medication to lifestyle changes, adherence is low”

“Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in many countries, and despite a wealth of evidence about effective prevention methods from medication to lifestyle changes, adherence is low,” says Professor Ulf Näslund, Umea University (Sweden). “Information alone rarely leads to behaviour change and the recall of advice regarding exercise and diet is poorer than advice about medicines. Risk scores are widely used, but they might be too abstract, and therefore fail to stimulate appropriate behaviours. This trial shows the power of using personalised images of atherosclerosis as a tool to potentially prompt behaviour change and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.”

3532 individuals who were taking part in the Västerbotten County (Sweden) cardiovascular prevention programme were included in the study and underwent vascular ultrasound investigation of the carotid arteries. Half (1749) were randomly selected to receive the pictoral representation of carotid ultrasound, and half (1783) did not receive the pictorial information.

Participants aged 40 to 60 years with one or more cardiovascular risk factors were eligible to participate.

“The differences at a population level were modest, but important, and the effect was largest among those at highest risk of cardiovascular disease, which is encouraging. Imaging technologies such as CT and MRI might allow for a more precise assessment of risk, but these technologies have a higher cost and are not available on an equitable basis for the entire population. Our approach integrated an ultrasound scan, and a follow up call with a nurse, into an already established screening programme, meaning our findings are highly relevant to clinical practice,” says Prof Näslund.

Importantly, the effect of the intervention did not differ by education level, suggesting that this type of risk communications might contribute to a reduction of the social gap in health. The findings come from a middle-aged population with low to moderate cardiovascular disease risk.