General physicians should avoid using inflammatory markers as non-specific tests to rule out serious underlying disease, suggests a new study

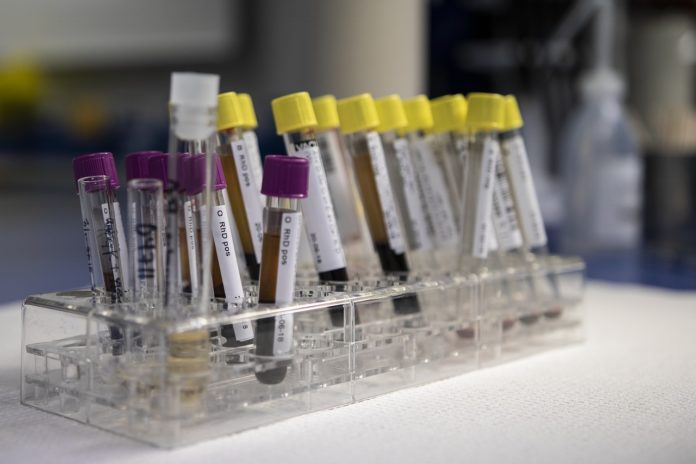

Blood tests that detect inflammation, known as inflammatory marker tests, are not sensitive enough to rule out serious underlying conditions. GPs should not use them for this purpose, according to new research published in the British Journal of General Practice.

Many diseases cause inflammation in the body, including infections, autoimmune conditions and cancers. Millions of inflammatory marker tests are done each year and rates of testing are rising. Although many of these tests will be done appropriately for different reasons, GPs are increasingly using them as a non-specific test to rule out serious underlying disease but there is no evidence to support this strategy.

The study found that the tests are not good at ruling out disease and false positive results are common, leading to more follow-on consultations, tests and referrals.

Using data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, the researchers analysed the records of 160,000 patients who had inflammatory marker tests in 2014 and compared these with the records of 40,000 patients who had not had the test.

For every 1,000 inflammatory marker tests performed, there would be 236 false positives, found the researchers. They also calculated that these false positives would lead to 710 GP appointments, 229 blood test appointments and 24 referrals in the following six months

Overall, 15 percent of raised inflammatory markers were caused by disease: 6.3 percent were the result of infections, 5.6 percent were caused by autoimmune conditions, and 3.7 percent were due to cancers. No relevant disease could be found in the remaining 85 percent of patients with raised inflammatory markers (‘false positives’).

For every 1,000 inflammatory marker tests performed, there would be 236 false positives, found the researchers. They also calculated that these false positives would lead to 710 GP appointments, 229 blood test appointments and 24 referrals in the following six months.

Half of patients with a relevant disease had normal test results, or a ‘false negative’, meaning that GPs should not rely on a normal test result as proof of good health or to ‘rule out’ disease.

In a second paper published in the British Journal of General Practice, the team, using the same data set, found that using two inflammatory marker tests does not increase the ability to rule out disease and should generally be avoided.

Dr Jessica Watson, a GP and lead author of the study, said: “While inflammatory marker tests can contribute to diagnosing serious conditions and are useful for monitoring and measuring response to treatment, their lack of sensitivity means they are not suitable as a rule-out test. False positives can lead to increased anxiety for patients, as well as increased rates of consultation, testing and referral.”