For long the question of how long a patient should be kept in the emergency after fainting has been an open one

A new study has found that that most causes of fainting due to serious heart rhythm disorders can be caught in the first six hours in Emergency.

For the first time, physicians in the Emergency Department (ED) have evidence-based recommendations on how best to catch the life-threatening heart conditions that make some people faint.

New research published in Circulation suggests that low-risk patients can be safely sent home by a physician after spending two hours in the ED, and medium and high-risk patients can be sent home after six hours if no danger signals are detected.

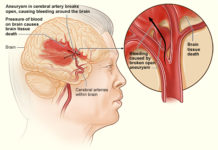

Fainting or syncope is a transient loss of consciousness due to acute impairment of blood flow to the brain with rapid, spontaneous and complete recovery. About one in three people suffer a fainting episode in their lifetime in the general population.

Fainting or syncope is a transient loss of consciousness due to acute impairment of blood flow to the brain with rapid, spontaneous and complete recovery. About one in three people suffer a fainting episode in their lifetime in the general population

Most cases of fainting is harmless, but a small percentage of people faint due to serious medical conditions, such as an irregular heartbeat, or arrhythmia. These arrhythmias usually come and go quickly, and the person’s heart rhythm returns to normal by the time the ambulance arrives or they reach the ED. Fear of these arrhythmias coming back have led to patients being kept in the ED for eight to 12 hours. However, only a small proportion of patients will experience a dangerous irregular heartbeat, heart attack or death within a month of fainting.

In this observational study, researchers used a simple tool to rank 5,581 patients from six EDs across Canada as low (0.4 percent), medium (8.7 percent) or high risk (25.3 percent) based on the risk of an arrhythmia within next 30 days.

Out of the 5,581 people, 74 percent were classified as low-risk, 19 percent as medium-risk and 7 percent as high-risk. One month after fainting, 3.7 percent of individuals (207) suffered an arrhythmia.

The team found that half of the arrhythmias were identified within the first two hours of arrival at the ED for low-risk patients, and within six hours for the medium and high-risk patients. They also found that 92 percent of the underlying arrhythmias were identified within 15-days among the medium and high-risk patients.

“We learned that irregular heartbeat called arrhythmias usually happen soon after fainting” said lead author Dr. Venkatesh Thiruganasambandamoorthy, an emergency physician and scientist at The Ottawa Hospital and associate professor at the University of Ottawa. “This means we can catch most of these events in those first few hours in the Emergency Department, where we can quickly give people the treatment they need. The types of arrhythmias that medium-risk patients suffer are important but non-life threatening, so these patients can be monitored from the comfort of their homes. A few days in hospital can be considered for high-risk patients,” he added.

The research team also found that medium and high-risk patients benefit from home heart rhythm monitoring for 15 days, which should ideally start when they leave the ED.